J.R.R. Tolkien didn’t offer many harsh opinions about his contemporaries. But in an unsent letter, he made an exception — writing that he disliked Frank Herbert’s Dune “with some intensity.”

On the surface, it’s a puzzling statement. Dune is a sweeping myth of prophecy and power, a richly built world with its own languages, genealogies, and histories. In many regards, it’s a natural cousin of The Lord of the Rings — a saga of destiny and leadership set against the fall of civilizations.

Tolkien didn’t explain his intense dislike, but it’s clear that Dune represented something else entirely. It proposed a vision of morality that felt dangerous — a world in which might makes right, and moral clarity is sacrificed for pragmatic ends.

And this vision couldn’t be any more at odds with that of Tolkien’s masterpiece…

Reminder: this is a teaser of our members-only deep dives.

To support our mission and get our premium content every weekend, upgrade to a paid subscription below. You’ll get:

Full-length articles every Saturday

Members-only video podcasts / interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art and philosophy breakdowns

Contrasting Moral Universes

Dune begins with a classic arc of betrayal and vengeance. House Atreides is destroyed by imperial treachery and Paul, the heir, escapes into the desert. He becomes a messianic figure among the Fremen, leads a rebellion, and eventually rises to the imperial throne.

It all sounds rather heroic — until you look closer.

Paul’s ascent is paved with ambiguity. To secure the future of his people, he unleashes a holy war that will span the galaxy and kill billions. He sees this fate coming in visions, and doesn’t want it — but he accepts it. The jihad becomes a necessary evil, justified by its outcome.

In other words, Paul embraces a consequentialist moral ethic: what matters is not whether an action is good or evil in itself, but whether it produces a favorable result. If suffering now leads to peace later, then the suffering is worth it. If violence now ensures stability, then violence is the price of order.

And he isn't alone. Many of the most influential works in modern fantasy follow this line. In A Game of Thrones, characters lie, murder, and betray — all in service of some fragile and weakly-defined “greater good.” In Dune, morality is a tool, bent to the will of those strong enough to shape the future.

This is precisely the opposite of how Tolkien saw the world.

In The Lord of the Rings, the most important actions are not the ones that succeed — they are the ones that are right. Frodo, for example, doesn’t know if he’ll reach Mount Doom, much less if he’ll even survive his quest. But he volunteers anyway:

“I will take the Ring, though I do not know the way.”

Frodo’s virtue lies precisely in his willingness to walk into the unknown, because even if he doesn’t know what will happen, he knows it’s the right thing to do. Frodo's quest is right because it resists evil, not because it's guaranteed to succeed.

Tolkien was, in modern terms, a deontologist: someone who believed that actions are moral or immoral based on their inherent nature, not on the result they produce. For him, a moral choice isn’t about calculation, but about faithfulness.

The contrast is stark. Paul Atreides embraces destiny by wielding power to reshape the world. Frodo embraces destiny by resisting power — and trusting that good may still come, even if he fails.

Power, Providence, and the “Long Defeat”

Few symbols in fiction are as potent as Tolkien’s Ring of Power. It tempts everyone who touches it, offering them total control and absolute victory. Even the wise, like Gandalf and Galadriel, refuse it out of fear they would become tyrants in trying to do good.

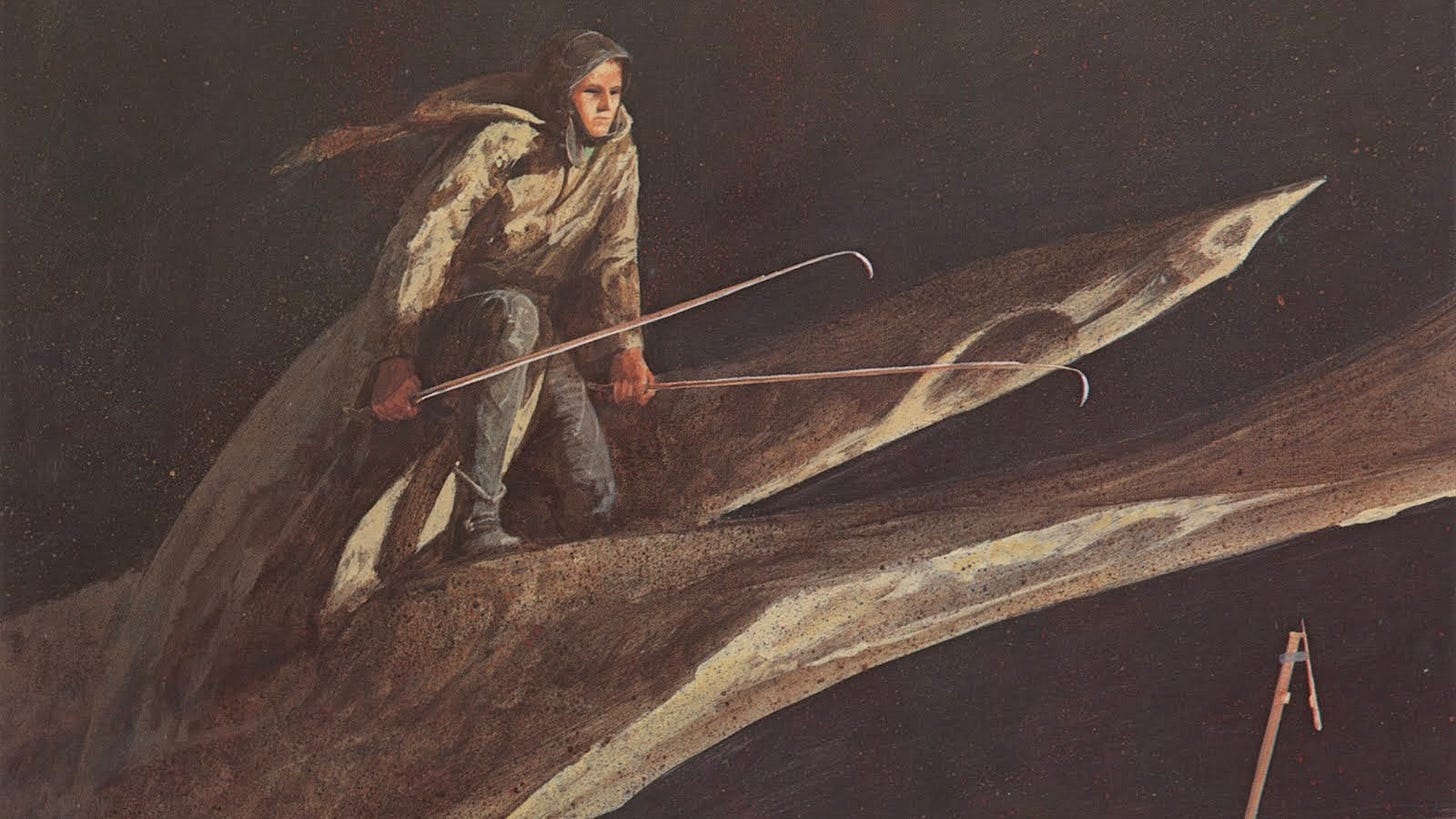

In Dune, Paul willingly takes the (metaphorical) ring and wields it. He leads, transforms, and conquers. The universe bends to his vision. He suffers for it, yes, and questions it, but he never truly rejects the call to rule.

Contrast this with the world of Middle-earth, where all Tolkien’s heroes do the opposite. When Frodo offers the Ring to Aragorn, he refuses. Even Samwise, humble as he is, feels the surge of the Ring’s power, and lets it go.

In Tolkien’s world, greatness lies in renunciation. True strength lies in restraint.

But the moral differences between the two stories run deeper still. Tolkien’s understanding of good and evil goes beyond the humility of his heroes, and into the very fabric of Middle-earth itself.

This is where his idea of the “long defeat” of history comes in…

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Culturist to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.