In today’s fast-paced world, the word “leisure” typically means little more than time off: weekends, vacations, or breaks from the grind. It’s seen primarily as a way to recharge, to rest before plunging back into work.

But in Leisure: The Basis of Culture, German philosopher Josef Pieper offers a far deeper and more transformative vision. For Pieper, leisure isn’t just a break from labor — it’s the foundation of all culture, the soul’s gateway to reality, and a necessary condition for human flourishing.

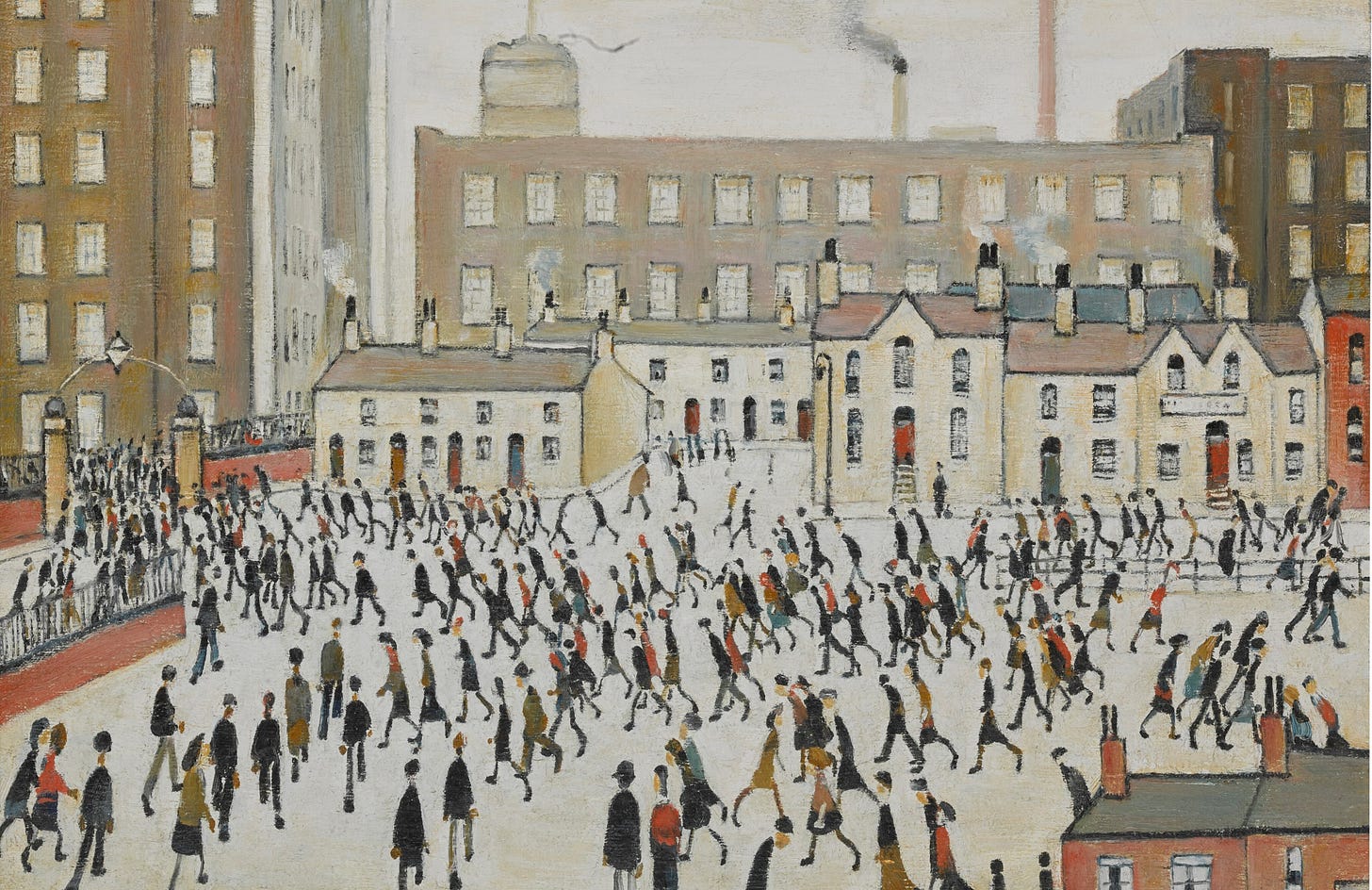

In his seminal work, Pieper challenges the modern world’s obsession with productivity, and warns of a “leisure-less culture of total work” where human worth is measured by output. In such a culture, even leisure is reduced to utility — a tool for becoming a more efficient worker.

But true leisure is something entirely different. It’s not passive relaxation, but active receptivity. Today, we explore how embracing it allows you to better encounter truth, beauty, and the divine…

Reminder, you can support our mission and get our members-only content every weekend: in-depth articles, podcasts and great book breakdowns.

This Saturday, we break down 10 essential works of literature that you MUST teach to your children — that will help them build a beautiful life...

Join as a member to read it, and help support our mission 👇

Breaking the Culture of Total Work

Pieper’s central critique is simple but profound. Modern society, he argues, has forgotten the true meaning of leisure. Instead, it has embraced a relentless “culture of total work,” where the value of a person is tied directly to their productivity:

The original meaning of the concept of ‘leisure’ has practically been forgotten in today’s leisure-less culture of ‘total work’: in order to win our way to a real understanding of leisure, we must confront the contradiction that rises from our overemphasis on that world of work.

-Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture

But the main problem isn’t work itself — rather, it’s the totalizing mindset that sees all of life through the lens of utility. In such an outlook, leisure is justified only if it serves work, functioning as mere recovery time to ensure future productivity. Having defined this primary error, Pieper then furthers his thesis by posing a critical question:

Can the human being be satisfied with being a functionary, a ‘worker’? Can human existence be fulfilled in being exclusively a work-a-day existence?

The consequences of one’s answer to this question are far-reaching. In a purely utilitarian culture, education becomes job training. Art becomes entertainment. Worship becomes performative.

In other words, everything bends toward utility, leaving little room for the contemplative, the beautiful, or the transcendent. The very foundations of culture — philosophy, art, and religion — begin to erode…

The Soul of Leisure

For Pieper, leisure is not the absence of activity but the presence of depth. It is a condition of the soul — an inner stillness that allows you to see reality clearly and engage with it fully.

In his words, “leisure is precisely the counterpoise to the image of the ‘worker.’” It is an attitude of openness, a willingness to encounter the world not as a resource to be used, but as a mystery to be contemplated.

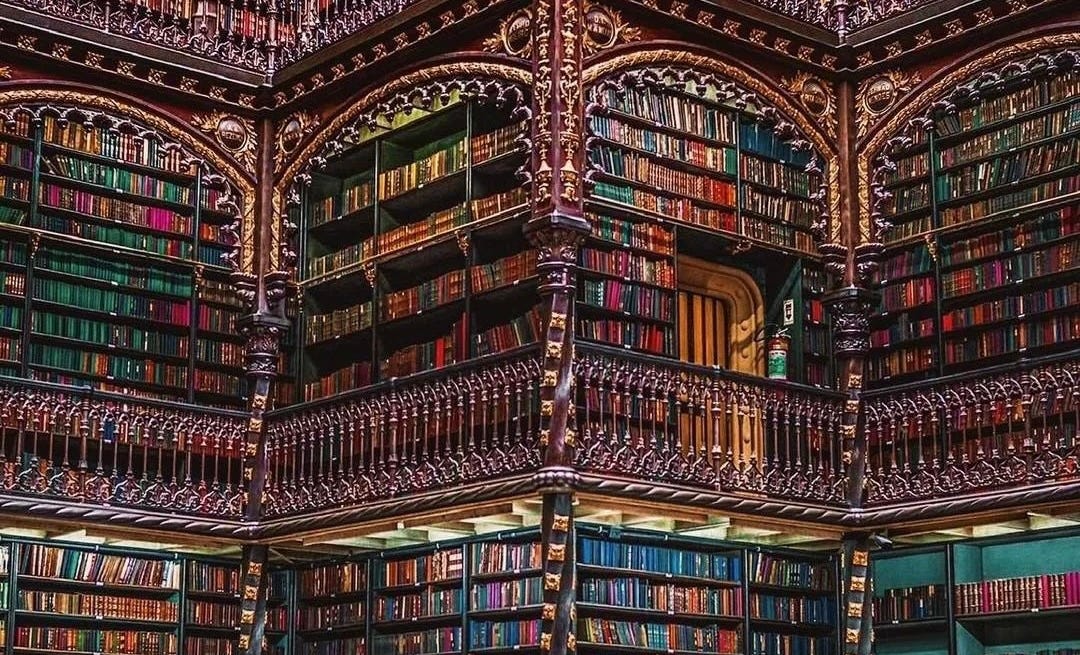

This contemplative leisure is the birthplace of culture. Philosophy, art, and religion all arise from the space that leisure creates — a space where you’re free to wonder, to create, and to celebrate. In the High Middle Ages, Pieper notes, it was understood that idleness wasn’t simply doing nothing, but refusing to engage deeply with existence.

Ironically, the modern workaholic, driven by restless busyness, may be the true idler. As Pieper writes, “the restlessness of work-for-work’s-sake arises from nothing other than idleness.”

Leisure also allows for festivity, which Pieper sees as another vital expression of human freedom. Contrary to how most parties are celebrated today, a true festival isn’t a break from life, but a heightening of it — it’s an affirmation of existence, of community, and of joy. In leisure and festivity, we encounter life not as a task to be completed, but as a gift to be received.

But engaging in true leisure isn’t easy. It requires the courage to step back from constant doing and to simply be. As Pieper notes:

The condition of utmost exertion is more easily realized than the condition of relaxation and detachment, even though the latter is effortless.

In a world that prizes busyness, cultivating the contemplative stance of leisure is a radical act.

Freedom, Education, and the Whole of Existence

Pieper’s vision of leisure has profound implications for how you understand freedom, education, and culture itself. In his view, leisure is not a luxury, but something essential to the full development of the human person. It’s in leisure that you encounter truth, beauty, and meaning — the things that cannot be measured or monetized, but are vital for human flourishing.

Education isn’t about producing workers, but nurturing souls. It’s about forming people who can contemplate, create, and celebrate — in other words, people who can see the whole of existence, not just its utility.

As Pieper writes, “the ability to be ‘at leisure’ is one of the basic powers of the human soul.” Without it, education becomes hollow, reduced to mere training for economic productivity.

Leisure also safeguards freedom. In the “total work” culture, people become functionaries, or cogs in a vast machine. Leisure breaks this cycle by allowing individuals to step back, reflect, and encounter themselves and the world anew. It preserves the dignity of the person by affirming that you are more than what you produce.

But perhaps Pieper’s most urgent message is this: you must learn how to be at leisure. It’s not something that happens automatically during time off. It requires intention and a willingness to cultivate stillness.

It’s a paradoxical discipline, in the sense that it requires effort to relax in a way that truly restores. But if you want to foster a deeper engagement with life itself, it’s absolutely necessary.

Recovering What’s Truly Human

While Pieper offers a sharp critique of modernity’s obsession with productivity, he also provides a hopeful vision of what it means to be human. “In leisure,” he writes, “the truly human is rescued and preserved precisely because the area of the ‘merely human’ is left behind.”

To recover leisure is to recover your humanity. It’s to remember that life is not simply meant to be worked through, but to be lived deeply, joyfully, and with reverence for the mystery that surrounds you.

In a world that often mistakes busyness for purpose, Pieper’s call to leisure is more urgent than ever — it’s a call to slow down, look around, and truly live.

Thank you for reading! 🙏

If you want to support our mission to uncover Truth, Goodness and Beauty, join as a paid subscriber and get access to our entire archive of members-only content.

This Saturday, we break down 10 essential works of literature that you MUST teach to your children — that will help them build a beautiful life...

P.S. Don’t Miss This!

If you enjoyed this article, check out the retreat Evan Amato (co-author of this Substack) is hosting in Italy this summer. It’s called Leisure: The Basis of Culture, and is designed to help you study and experience Pieper’s seminal work in person.

Over the course of a week, you’ll visit the hidden jewels of northern Italy — including Milan, Bergamo, and Lake Garda. As you do so, you’ll learn the secrets of how to slow down and embrace leisure as the gateway to both meaningful living, and the contemplation of the divine.

Click here to learn more about the retreat. Spots are limited, so be sure to apply today — you don’t want to miss out on this once-in-a-lifetime experience!

“The modern workaholic is the true idler” — a brilliant remark

Awesome essay here! I read Pipers book a couple years ago and have been pondering his message for a while. It was actually one of the reasons I decided to change my college major from business to classical liberal arts and humanities. (Luckily I’m at a conservative school so I don’t get any critical theory)

People ask me all the time, “what are you going to do with that degree?” I’m not always sure how to answer their question because of its utilitarian assumption. How about “become wise” or “fill my soul” for an answer? Of course I do still need to figure out how I will support myself financially but I have faith it will work out.

“Seek ye first the kingdom and then these things shall be added unto you”