In 1812, the Brothers Grimm published the first version of Snow White in their Children’s and Household Tales. It bore many of the elements we still recognize today, such as the magic mirror, the dwarfs, and the poison apple.

But the original Snow White was far from a simple love story — it was a cautionary tale about envy, survival, and the brutality of justice.

Before Snow White was a princess in a glass coffin, she was a child marked for death.

Today, we look at how this classic tale has transformed over the ages, and how its plot and symbolism compare to Disney’s sanitized adaptation…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only video podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art and philosophy breakdowns

A Fairytale Without Romance

The story of Snow White begins with a queen sewing beside a window in winter. She pricks her finger and watches a drop of blood fall onto the snow. Wishing for a child “with skin as white as snow, lips as red as blood, and hair as black as ebony,” she soon gives birth to such a daughter, but dies shortly after.

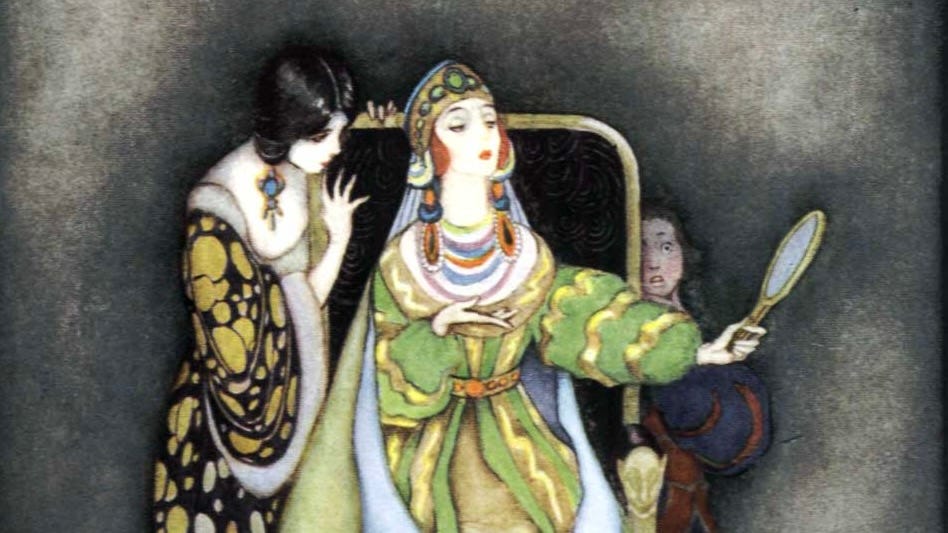

The king then remarries a woman who is beautiful, proud, and obsessed with her own appearance. She consults a magic mirror daily, asking who is the fairest in the land. For years, the answer is always the same — she is.

But when her stepdaughter turns seven, the mirror gives a new answer. The young child, Snow White, has surpassed her in beauty.

As a result, the queen orders a huntsman to take the girl into the woods and kill her, demanding Snow White’s lungs and liver as proof of her death. Though the huntsman leads the young girl away, he can’t bring himself to kill her — he instead lets her escape into the forest, and kills a wild boar in her place. He brings back its organs to the queen who cooks and eats them, believing she has consumed her rival.

As the young Snow White flees into the forest, she eventually finds shelter in a cottage belonging to a group of dwarves. They allow her to stay with them in exchange for cleaning and cooking, to which she agrees. The dwarves also warn her to never let her guard down, and to never speak with strangers.

After several years, the queen learns that Snow White is still alive. Disguising herself as a peddler, she ventures into the forest and attempts to kill her stepdaughter. Snow White, disobeying the instruction to not speak with strangers, entertains her guest — not just once, but on three separate occasions.

The first time, the queen deceives Snow White by giving her a special lace bodice. Helping her don the garment, she then tightens it until the girl collapses. Snow White lays dying, gasping for breath — but fortunately, the dwarfs arrive just in time to save her.

On the second occasion, the queen returns with a poisoned comb. She strokes it into Snow White’s hair, and the girl falls deathly ill. Yet once more, the dwarfs arrive in time to remove the comb from her hair and save her.

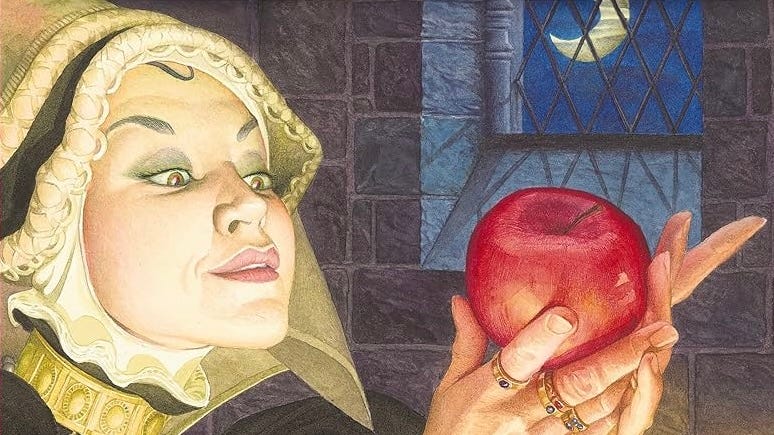

On the queen’s third and final visit, she offers Snow White a poisoned apple. But crucially, she guesses Snow White will be skeptical. As such, she laces half the apple with poison, and eats the harmless side to prove it’s safe. Trusting the stranger again, Snow White takes a bite and drops dead.

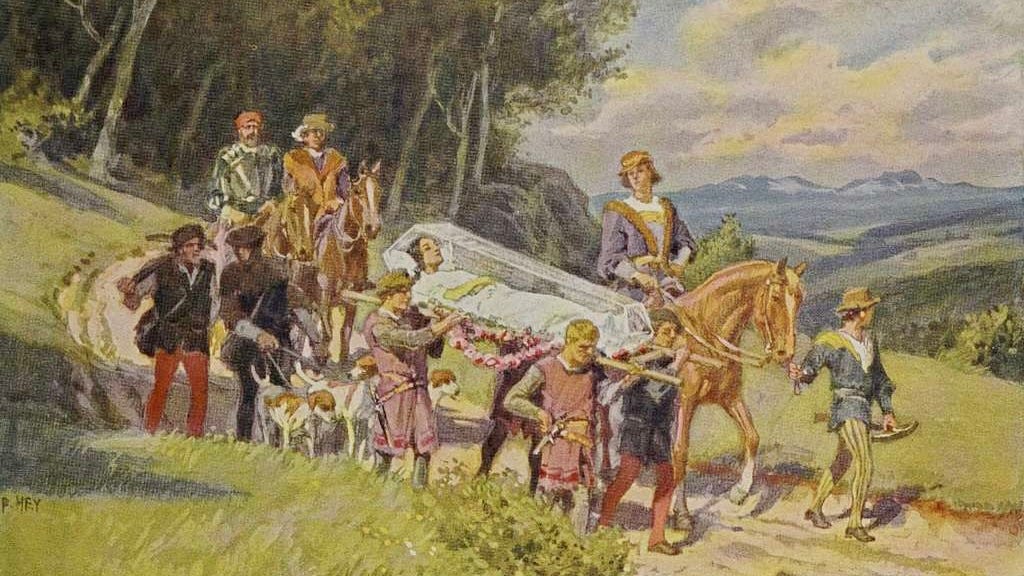

The dwarfs, arriving too late to save her, place Snow White in a glass coffin. One day, a prince comes across the coffin and begs to take it with him. As his servants carry it off, they stumble — the coffin falls, and a chunk of the apple dislodges from Snow White’s throat. She awakes, and accepts the astonished prince’s marriage proposal.

But the story ends with revenge, not a kiss. The queen, having been told by her magic mirror that a bride-to-be is now the fairest in the land, attends the wedding to see who it is. Discovering the girl to be Snow White, she plots chaos once more — but not before the bride informs her groom of the queen’s true nature.

The prince then apprehends the evil queen and forces her into red-hot iron shoes, condemning her to dance until she dies. They watch on as the queen breathes her last, and the story ends.

A World of Symbols

So what are you supposed to make of such a story? In large part, the key to understanding it lies in the power of symbols incorporated throughout.

The mirror, for example, speaks to a world where beauty is more than just appearance, but authority. As soon as the queen is no longer the “fairest,” her status is threatened.

The lesson it reveals is about more than jealousy — it’s about the murderous lengths people will go to to preserve their power and status.

The symbol of the apple carries even older weight. It’s rich with deep biblical resonance, calling to mind temptation, fall, and exile from Eden. But here, Snow White isn’t tempted by knowledge or rebellion. She’s simply lied to by someone who claims to want what’s best for her.

The apple is beautiful, glossy, and designed to disarm. In taking a bite, Snow White isn’t punished for defiance — she’s punished for trust.

Even the forest itself is rich in meaning. It’s not only a place of exile — a space outside society’s control — but also one of transformation. Snow White goes into it as a hunted child and emerges, metaphorically, through death and resurrection. In many stories, forests mark the boundary between the known and the unknown, the civilized and the wild. They are liminal spaces in which a character must either mature, or vanish.

Finally, there’s the queen’s punishment. She isn’t merely defeated, but humiliated — made to dance to death in red-hot iron shoes. It’s a ritual of public justice in which evil isn’t just removed, but is put on display for all to see.

In the words of the English statesman George Saville, “men are not hanged for stealing horses, but that horses may not be stolen.” It is fair to say the Grimm Brothers would have agreed with this sentiment.

What Disney Left Out

In 1937, Walt Disney released Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, the first full-length animated feature film. While the plot of the original story remained familiar, the tone shifted completely.

For starters, the violence was softened. There’s no cannibalism, and the queen’s first two attempts to kill Snow White — with the bodice and the comb — completely disappear. Instead of dancing to death in iron shoes, she simply falls to her death in a storm.

The dwarfs are substantially different as well. In the Grimms’ version, they have no names and little personality, but in Disney’s version they are funny, endearing, and central to the story’s emotional rhythm.

Snow White is made more innocent, too. In the Grimms’ tale she flees, bargains, and works to earn her shelter. But in Disney’s version, she simply sings to animals and waits to be rescued.

Lastly, the prince — who is barely present in the original — is now the one who revives Snow White with a kiss. The film ends not with punishment, but with romance.

It would be unfair to say Walt Disney erased the original. But he certainly sanitized it, reshaping it into something that would comfort and not disturb. In so doing, he introduced millions to Snow White.

But he also left something behind — the danger, the ambiguity, and the sense that children’s stories were once meant to warn, not reassure…

Reminder: you can support our mission and get tons of members-only content for a few dollars per month 👇

Full-length articles every Wednesday and Saturday

Members-only video podcasts and exclusive interviews

The entire archive of great literature, art and philosophy breakdowns

Brilliantly told and long overdue. The original “Snow White” is no bedtime story. It is a gothic parable of power, paranoia, and psychological metamorphosis dressed in the trappings of folklore. What you’ve done here is peel back the cellophane layer of Disney gloss to expose the raw sinew of the tale’s darker truths. Now people might understand.

The idea that beauty in the Grimms’ version is not passive currency but active threat is crucial: beauty as a locus of power that must be controlled, even destroyed. This isn’t romance, it is a generational power struggle: the aging queen clings to symbolic capital while the child becomes an existential menace the moment she surpasses her. Freud would have a field day!

What’s more fascinating, though, is how Snow White’s resurrections (three near-deaths) form a proto-initiation ritual. She’s not just surviving;m, she’s being forged. The poisoned apple isn’t just biblical, it is mythic, even shamanic. Across cultures, the descent into symbolic death is how wisdom, maturity, and rebirth are achieved. This tale, in its raw form, belongs not to the genre of romance but of rites of passage.

Disney’s rendering, by contrast, makes Snow White less a heroine than a helpless doll in a musical terrarium. The forest no longer threatens, it sings. The queen is no longer a terrifying lesson in tyranny and vanity, but a cartoon villain with thunder effects. In stripping the story of its terror, Disney inadvertently stripped it of its depth. Sadly.

We forget that fairytales weren’t invented to comfort children, but to prepare them for violence, for loss, for betrayal, for ambiguity. They’re not promises of happy endings, but survival manuals encoded in metaphor.

Perhaps it’s time to give children back their monsters, and teach them how to outwit them.

Grimm's works should be required reading in high school and for literature majors as well.